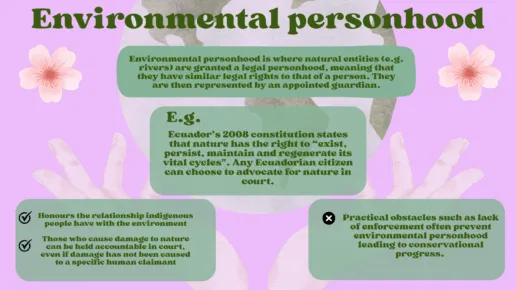

Environmental personhood is a concept which emerged from the Rights of Nature movement. It assigns a legal personhood to a natural entity, meaning that entity has rights and can be represented in court by guardians. In 2008, Ecuador became the first country to implement the Rights of Nature into its constitution, meaning that any citizen can sue on the behalf of nature’s rights. Whilst there is still some ambiguity about whether environmental personhood can be successfully enforced to create measurable, positive impacts, I would argue that its most significant benefit is as a catalyst for cultural change. Many indigenous societies view nature in a completely different way to the Western conception of it as resource – they view themselves as part of it, meaning it must be protected for the sake of itself. Therefore, environmental personhood could encourage Western societies to adopt indigenous, ecocentric values, inspiring a more effective nature recovery movement.

Environmental personhood as a catalyst for cultural change

Despite Ecuador’s 2008 constitution leading to limited direct positive impacts on nature recovery, it did spearhead the Rights of Nature movement which now has been implemented in many countries including New Zealand, Bolivia, Canada and Spain. The rising popularity of this movement signifies a cultural shift: from viewing nature as a resource to humans (anthropocentric) to viewing it as deserving to exist within its own right (ecocentric).

In 2019, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) issued a report which found that transformative change across economic, social, political and technological factors is required to meet sustainability targets. This has led many environmentalist thinkers to suggest that a cultural shift is required to make this transformative change. Therefore, perhaps environmental personhood’s greatest asset is not its ability to directly enact nature recovery outcomes but rather its ability to influence the way Western culture thinks about nature, which will in turn lead to nature recovery outcomes.

Case Study: How successful was Ecuador’s constitution in protecting nature?

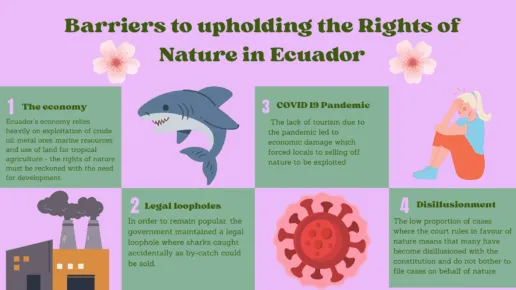

In Ecuador’s landmark 2008 constitution, nature is given the right to “exist, persist, maintain and regenerate its vital cycles”. Whilst there have been some lawsuits since which have enforced the Rights of Nature (e.g. Los Cedros Forest being protected against gold mining), these have been limited in number, raising questions about the efficacy of the Rights of Nature as a conservation strategy. For example, Ecuador’s attainment of the UN’s sustainable development goals 14 and 15 (pertaining to protecting marine and terrestrial nature) has either remained stagnant or decreased, since 2008. Additionally, extractive industry has increased, and iconic features of nature have failed to be protected: the San Rafael waterfall was destroyed by the Coca-Codo Sinclair hydroelectric project. The reason for the constitution’s limited success has been due to multiple barriers: attempting to balance nature’s rights with the need for economic development, the disincentive of legal costs for advocates, and a growing sense of disillusionment due to low success rates of protecting nature.

Environmental personhood as a catalyst for cultural change

Despite Ecuador’s 2008 constitution leading to limited direct positive impacts on nature recovery, it did spearhead the Rights of Nature movement which now has been implemented in many countries including New Zealand, Bolivia, Canada and Spain. The rising popularity of this movement signifies a cultural shift: from viewing nature as a resource to humans (anthropocentric) to viewing it as deserving to exist within its own right (ecocentric).

In 2019, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) issued a report which found that transformative change across economic, social, political and technological factors is required to meet sustainability targets. This has led many environmentalist thinkers to suggest that a cultural shift is required to make this transformative change. Therefore, perhaps environmental personhood’s greatest asset is not its ability to directly enact nature recovery outcomes but rather its ability to influence the way Western culture thinks about nature, which will in turn lead to nature recovery outcomes.

Environmental personhood: a concept inspired by indigenous cultures

Environmental personhood is a concept which borrows heavily from certain indigenous cultures’ beliefs towards nature.

- For example, the assigning of legal personhood to the Whanganui River in New Zealand aligns with Māori beliefs of rivers and mountains being their ancestors. This importance ascribed to nature and the sense of being one with it is further demonstrated by the Māori saying “Koauteawa, koteawakoau” which means “I am the river, and the river is me”.

The Māori ecocentric view of nature differs from the typical Western anthropocentric attitude towards nature as a resource. This is similar to other indigenous cultures such as the Innu of Canada.

- For example, Chief Jean Charles Piétacho (of the Ekuanitshit council) says that “In defending nature, we are defending ourselves, because we are an integral part of nature.”

The importance of not overgeneralising indigenous cultures

Whilst assigning environmental personhood/ rights to nature aligns with some indigenous cultures and has helped to repair injustices inflicted upon them, it is important not to overgeneralise indigenous cultures since they are so diverse. Not all indigenous groups relate in the same way towards nature, and in fact some do not have particularly pro-environmental cultures at all.

- For example, in Malinowski’s 1935 ethnography of Trobriand Islanders, he found that they had a tradition of growing a huge surplus of yams and then leaving them to rot outside their homes as a testimony to their wealth.

Kay Milton (a professor of social anthropology) calls the tendency for environmentalists to assume all indigenous cultures have a special connection with and knowledge of nature the “myth of primitive ecological wisdom”. Regardless of the fact that this assumption is incorrect, it is also harmful in the sense that it may cause indigenous groups to feel that they must lean into the stereotype in order for their culture to be valued in society. Additionally, the idea that all indigenous groups have “ancient” ecological wisdom which means they are more in touch with nature can contribute to the theory of “unilinear cultural evolution”. This was a theory popular amongst early anthropologists who believed that indigenous hunter gatherer societies were evolutionarily behind Western societies, and that they would eventually evolve into Western societies, which were considered the pinnacle of human development. This theory has widely been debunked as racist since it portrays indigenous societies as “primitive savages” whose culture is “backward” and less valuable than Western ones. It is also completely incorrect since it is ethnocentric and ignores the existence of indigenous history.

Environmental personhood as an avenue for respecting indigenous rights: still a way to go

The implementation of environmental personhood/Rights of Nature has led to some considerable successes for indigenous people’s rights. For example, the Whanganui River in New Zealand was appointed two legal guardians: one from the government and one representing the Māori. This guardianship of the river honours Māori culture as well as helping to compensate the Māori for historical colonial oppression, such as the handing over of sovereignty of the land to the Crown via the Treaty of Waitangi.

However, despite these successes, some aspects of implementation of Rights of Nature have been criticised by indigenous groups across many different countries.

- Indigenous groups were not consulted before development projects began as a response to Bolivia’s 2009 Framework Law on Mother Earth and Integral Development for Living Well.

- Māori have criticised the Western language used to monitor conservation targets and progress for Te Urewera (another natural entity granted legal personhood in New Zealand).

- The Ecuadorian indigenous population were not granted the right to govern their own land which is what they wanted.

Furthermore, since indigenous people tend to be staunch and vocal advocates for enforcing the Rights of Nature, they are more likely to suffer from violence as a result. In 2021, 40% of the victims of violence perpetrated against environmental activists were indigenous people, which is disproportionate.

- For example, Eduardo Mendúa, an Ecuadorian indigenous leader, opposed an oil extraction project by the state-owned oil company Petroecaudor EP, and was subsequently murdered by hitmen. He had argued that the project had begun without proper informed consent of the indigenous people living there. The project began within the context of President Guillermo Lasso breaking previous promises and investing in oil and mining to try and tackle country’s debt.

Conclusion

In conclusion, whilst the implementation of environmental personhood and the Rights of Nature may result in some direct positive nature recovery outcomes such as successful lawsuits against the exploitation of nature, the most significant impact is the cultural change that can come out of it. Many indigenous cultures have ecocentric values which if they were adopted into Western society, could be the cultural shift we need to drive wide-scale nature recovery in the face of climate change, mass extinction and destruction of nature. If natural entities are recognised as people legally, society may begin to not only view nature as important to protect but as an integral part of being alive, as many indigenous societies already do. However, it is vital that the expansion of the Rights of Nature occurs alongside the expansion of the rights of indigenous people – environmentalists should aim to listen to indigenous voices and consider their wishes when implementing conservation strategies.