We are delighted to announce that Yadvinder has been awarded the prestigious Ramon Margalef Prize in Ecology, one of the world’s foremost honours in ecological science.

Presented annually by the Government of Catalonia, the prize recognises an exceptional scientific career or groundbreaking discovery in ecology or environmental sciences. Since its inception in 2004, it has celebrated a distinguished list of global ecologists.

The jury commended Professor Malhi for his pioneering research on tropical forest ecosystems, particularly for integrating functional and biodiversity perspectives and for his leadership in developing long-term ecological research networks across the tropics. The award also honours his commitment to global equity in science, including his efforts to support researchers in the Global South through collaborative and inclusive approaches.

In this blog he reflects on his week in Barcelona as a guest of the Catalonian government and the University of Barcelona.

Homage to Catalonia: In the Shadow of Ramon Margalef

This past week in Catalonia I was honoured to receive the Ramon Margalef Prize for Ecology from the Government of Catalonia. It was wonderful to celebrate that prize in a week admirably coordinated by the Catalonian government and the University of Barcelona, but it was also an opportunity to reflect on Ramon Margalef, a foundational figure ecology and the first Professor of Ecology in Spain, to revisit his prescient ideas and enduring legacy.

The visit began in the holm oak forests of the Prades nature reserve, south of Barcelona, forests that blanket the hills of Catalonia. These forests have long histories of human entanglement and management for charcoal, but has charcoal extraction declined they have been shifting and expanding in the face of rural agricultural abandonment, providing opportunities for nature recovery but also increased fire risk as wood fuel builds up and the climate dries. Hosted by the indominatable Prof Santiago Sabate Jorbe, a former student of Margalef, we visited long-term ecological experiments that have been running since the late 1990s, where 30 percent of rainfall has been excluded to mimic chronic drought. The results tell a layered story: as conditions dry, shrubs begin to outcompete oaks, photosynthesis and productivity decline, and some trees die. Yet those that survive seem to cope with the remaining resources. The forest thins but does not collapse. Even under stress, ecological energy continues to flow. It was a living demonstration of a key ecological insight about responses to change: the ecosystems shift, that resilience emerges not from static permanence, but from adaptation.

That theme resurfaced the next day at the University of Barcelona, where I gave a public seminar on energy flow and ecosystems, from the fine scale of forest metabolism in single sites to the planetary scale of the biosphere. I framed the talk around the writings of Ramon Margalef, liberally sprinkling my talk with his quotes. Half a century ago Margalef re-imagined ecosystems as thermodynamic systems shaped by the flow of energy and information. At the dawn of the discipline of systems ecology, he was already linking the physics of energy with the creativity of life. I had not read his work in depth before finding our I had been awarded the prize. He is widely read in Iberia and Latin America, but I think underappreciated in the English-speaking world (or that may just reflect my lack of formal undergraduate education in ecology).

Reading his work now, I was struck by how contemporary it feels. Margalef explored how ecosystems evolve toward efficiency, how disturbance reorganises complexity, and how diversity underpins stability, how disturbance is a font of renewal and ecological creativity, themes that still drive ecological thought today. In his view, nature’s patterns are not static hierarchies but dynamic negotiations between energy, matter, and form.

The audience discussions that followed (two hours of them!) were searching. With faculty and students, we explored not only the science, such as how to quantify energy flows and their relevance for ecological resilience, but also the philosophy behind doing ecology in modern times: how to keep curiosity alive amid environmental anxiety, and how to communicate and share ecological insight beyond the academy and how to engage with wider society. In a later session with early-career researchers the conversations turned to career paths in ecology the ecology and political engagement, the relationship between activism and science, and the challenge and necessity of sustaining optimism in challenging geopolitical times.

That evening, my son and I were invited to attend Philip Glass’s opera stunning opera Akhnaten at the Gran Teatre del Liceu, a work that turned out to echo some of the day’s themes with uncanny precision. The opera is a meditation on political hubris and the transience of human ambition, but also at times a prayer on the enduring power of the sun and of sunlight, the overwhelming source from which all life’s energy flows. In one unforgettable scene, the small figure of the pharaoh stood silhouetted against a vast red solar orb, singing his hymn to the sun. The music, words and imagery captured what I had spoken of that morning: sunlight cascading through every living form, the biosphere as an intricate choreography of captured sunlight. It was science refracted through art, an emotional expression of the same truth.

The next morning brought a conversation with high school students from Catalonia’s Green Schools Network, ninety minutes of bright, initially timid but ultimately fearless questions about nature in schools and cities, sustainability, technology, and what it means to live within planetary boundaries. Their imagination and enthusiasm was heartening . It was a reminder that ecology, at its core, is also an education in awe and wonder and in agency to understand respect and shape the world.

Later that day, a visit to the CosmoCaixa Science Museum offered a more expansive reflection. The exhibits wove together cosmic evolution, the emergence of life, and the frontiers of human understanding, a seamless continuum from starlight to ecosystems. It felt perfectly aligned with Margalef’s conviction that the boundaries between physics, biology, and society are porous.

An impressive replica of a flooded Amazonian forest showcased ecological connectivity, in this case between forest and river and fruit-eating and seed-dispersing fish wound their way through flooded trees.

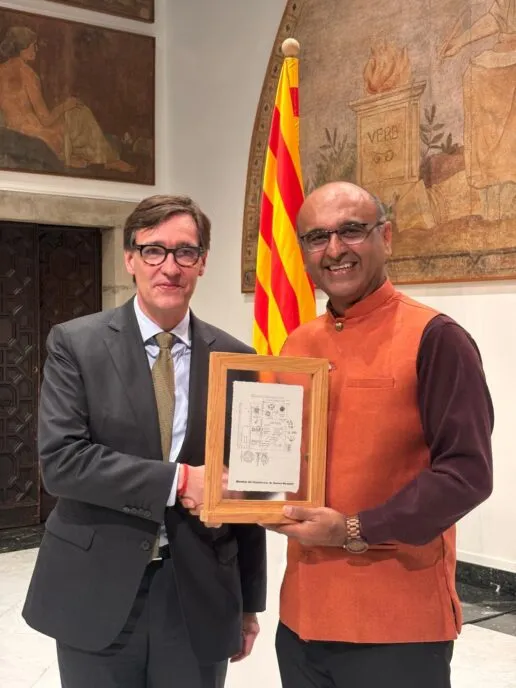

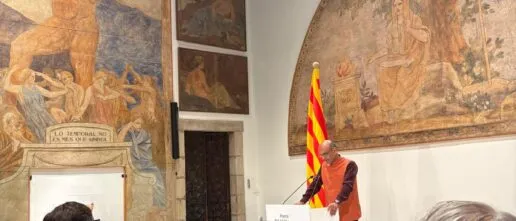

The week culminated with the award ceremony at the Palau de la Generalitat, the presidential palace in Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter. The setting, a confluence of medieval archicture framed by contemporary minimism, splashed with modern art and bathed the Barcelona’s luminous evening light, embodied a Catalan ability to honour tradition while renewing it.

The evening carried a personal grace note that moved me deeply. The introduction to the award was given by my former post-doctoral researcher and long-term friend, Imma Oliveras, who offered a generous and heartfelt tribute. She spoke not only of the science we had shared, but of a way of being in the world, of curiosity, patience, and the quiet joy of a whisky and a night sky after long days in the field. It was a reminder that science is also a human craft, built from relationships, humility, awe and wonder.

In my acceptance remarks, I reflected on Ramon Margalef’s extraordinary legacy as a scientist who reimagined ecology as a study of flows of energy, information, and relationship. He saw ecosystems not as static collections of species but as evolving systems that build order through the circulation of energy and that renew themselves through disturbance. This systems view feels profoundly relevant today, when both nature and society are undergoing rapid transformation and where loud political voices seek to reject diversity and the richness it brings. Ecology, at its best, teaches us that disturbance can be creative, that resilience is not resistance to change but the capacity to adapt and reorganise, and that diversity and cooperation underpin stability. Margalef’s great gift was to unite disparate parts of science with philosophy and poetry, to show that life itself is a dialogue between energy and form, and that our challenge as humans is to live wisely within the flows of the living world.

Meeting Margalef’s family afterwards brought that message home. His children and grandson spoke with affection of his legacy, curiosity, and humanity. It was moving to see how deeply his influence still runs through Catalan science, through the many faculty and senior researchers who were his students, not as nostalgia, but as living continuity.

As Margalef once wrote, "L’ecologia demana que mirem la natura una i altra vegada amb ulls d’infant." Ecology, he said, asks us to look at nature again and again with a child’s eyes. If we can keep those eyes open — curious, humble, and full of wonder — then perhaps we can learn, once more, how to live well within the living Earth.

Leaving Barcelona, I felt both grateful and pleasantly exhausted. The week had offered not only a glimpse of Catalonia’s vigorous ecological community but also a reminder of what ecology can still be at its best, a meeting point of knowledge, creativity, and care. Margalef’s voice, still echoing through the university buildings, libraries and offices, reminds us that ecology is not just a method for understanding life, but it can be a way of participating in it.

As I leave the vibrant city of Barcelona, I think again of backdrop of ancient hills cloaked in oak forests drawing in the late afternoon translucence, I picture again that vast red sun in Akhnaten, and I recall Margalef’s line, that ecology is “the study of systems that learn how to live together.” The forests, the scientists, the students, the politicians, the opera, the ceremony and even the President all seemed to echo that truth to me that week. It remains both the challenge and the promise of our time.

Related News Articles

Yadvinder Malhi awarded prestigious Ramon Margalef Prize in Ecology

Leverhulme Centre for Nature Recovery Director, recognised for outstanding contribution to the field of Ecology.

Professor Yadvinder Malhi’s Ramon Margalef acceptance speech

Presented annually by the Government of Catalonia, the prize recognises an exceptional scientific career or groundbreaking discovery in ecology or environmental sciences. Since its inception in 2004, it has celebrated a distinguished list of global ecologists.