As an intern with the LCNR, Diana researched about the concept of giving legal personhood to nature and whether this enables nature recovery. While she was initially sceptic about this initiative, as she traced the movement’s cultural roots, Indigenous perspectives, and economic implications, her view began to shift. Diana’s reflection doesn’t offer answers, but it does highlight why RoN matters in the broader green transition. It is one tool among many, helping us reimagine economies, policies, and daily choices that can align with the living world.

In childhood, the aliveness of nature often felt self-evident. The biosphere seemed vibrant, communicative, and full of personality. Yet for many of us raised in Western societies, that openness faded. The word environment came to replace the living world, flattening its richness into something external, separate, and abstract. In the process, we became estranged from the sense of kinship we once felt within nature, so lost the sense of responsibility to protect it.

Biologist E.O. Wilson captured the consequences of this estrangement when he warned that we are entering what he called the Eremocene: the ‘Age of Loneliness’. Not a loneliness from each other, but the “solitude of one species which is left, as a consequence of its own actions, isolated on the Earth”. The question is whether we can recover that uncorrupted relationship with nature from childhood, and in doing so, avoid a future of ecological isolation.

How Nature became a resource

My exploration of the Rights of Nature (RoN) movement began with a similar scepticism that many encounter when they first hear of it. The idea that ecosystems could be treated as legal persons seemed utopian, impractical. As a student of Biology, I become accustomed to engaging with new knowledge from a pragmatic view. A scientific teaching of nature can often reinforce the separation of humans from the living world, as we begin to ‘understand’ it from data and statistics, rather than our experience of it.

Yet as I delved deeper into the concept, my perspective started to shift. Christopher Stone, who first popularised the idea in Should Trees Have Standing?, argued that “until the rightless thing receives its rights, we cannot see it as anything but a thing for the use of ‘us’.” In other words, law shapes perception, and is a powerful storyteller: if nature is rightless, it is property; if it has rights, it becomes a subject of moral and legal concern.

Erich Zimmermann’s observation that “resources are not, they become” suggests that what we call a resource is not fixed. The same material may be waste at one point in time and wealth at another. If resources can “become”, they can also “un-become”, and perhaps this reframing is essential to reimagining an economy that does not exhaust the living systems on which it depends.

Writer Robert Macfarlane makes a similar point in Is a River Alive?. He observes that the “meaning of ‘river’ is now one of service provider”, a label reinforced by both infrastructure and imagination. We have become, he writes, “increasingly waterproofed: conceptually sealed against subtle and various relations with rivers”. This points to the way in which modern life has obscured our relational ties to the more-than-human world. Therefore, recognising the RoN and shifting definitions encourages a rethink of how human society is run.

A culture shift

As I read further, especially about Indigenous perspectives that describe natural entities as kin rather than resources, I began to see how the RoN movement invites us to see our interconnectedness with the living world. Around the same time, I was reading Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics, which argues for a model of human prosperity that operates within ecological boundaries. The connections between the two frameworks became clear. Both challenge the extractive logic of mainstream economics and call for systems aligned with the flourishing of life.

Gradually, I came to view the RoN not as idealistic but as a cultural catalyst. It is not only about legal text but about reviving our perception of aliveness, animacy, and relationship.

Questions and doubts

And yet, as I examined specific legal frameworks and court cases, doubts resurfaced. Does fitting nature into the human-made category of “legal person” risk reinforcing the very separation we seek to dissolve? I started to question whether rivers and forests have to adapt to our legal abstractions in order to be respected. And by recognising potential pitfalls in this approach, I began to explore what alternatives we have for more effective ecological restoration. Perhaps a more productive approach is to focus government efforts on dismantling harmful policies, such as fossil fuel subsidies, and redirecting investment toward regenerative practices and technologies. Such measures may present a greater leverage than legal innovations that risk being symbolic without enforcement.

This does not negate the value of ecological jurisprudence. It can be a crucial first step, but one that is difficult to implement, especially in economies still reliant on resource extraction. Moreover, the cultural shift RoN inspires, reframing nature as kin rather than commodity, is deeply powerful in changing dominant degrading systems and decision-making. But the legal mechanism may not be the only, or even the most effective, path to achieve it.

Conclusions

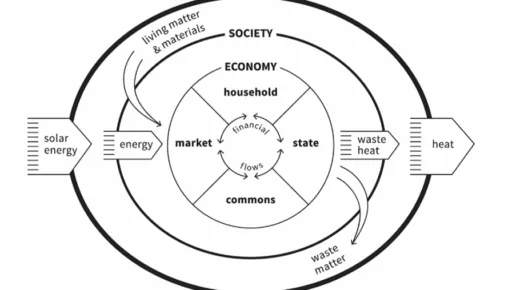

To conceptualise the contribution of ecological jurisprudence to promoting sustainable societies, we can take economist Kate Raworth’s invitation to See the Big Picture. As one of the chapters in Doughnut Economics, it explains the framework of an Embedded Economy (see Figure below), where the economic system is made up of: the market, the household, the commons and the state. These are ways of provisioning, but also the channels through which we can rethink our relationship to the living world. We can shift markets towards Natural capital, base the actions of households on principles such as ‘buen vivir’, steward the commons, and push for state recognition of the rights of nature. Therefore, granting legal personhood to natural entities is only one of the levers to be pulled for the transition to societies aligned with attributes of the living world.

My journey of engaging with the topic of legal personhood for nature went from perceiving it as unrealistic, to recognising its role as a powerful cultural lever, as it highlights the need to restore humans’ relationship with nature. We might not need a court ruling to recognise that a river is alive. We can choose to see it as such, to advocate for its protection, and to embed that recognition in the systems we design. Establishing rights for nature may open the door but perhaps focusing on redesigning our economic and financial structures to serve life, rather than demand that life conform to human categories, is the larger, more urgent task.