2025

Summary

A snapshot of the performance of Biodiversity Net Gain in England

- Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) creates a mandatory requirement for nearly all construction projects to measure and improve biodiversity, making it one of the most ambitious ecological compensation policies in the world.

- Effective governance of BNG is essential to ensure that uncertain future biodiversity gains materialise. BNG is measured using a habitat-based metric, so further species-based monitoring and mitigation is needed for optimal environmental outcomes.

- Developers must compensate for biodiversity loss: first on-site, and then by purchasing off-site units once on-site actions have been exhausted. Recent evidence suggests that demand for off-site units is potentially lower than expected (Duffus et al., 2025b).

- At a local level, communities’ acceptance of BNG measures is dependent on factors such as public access and species richness of habitats (Butler et al., 2025).

- Beyond England, BNG is globally influential, with its statutory biodiversity metric being adapted for countries including Sweden, Oman, Saudi Arabia, the U.S. and Singapore (Duffus et al., 2025a).

What is Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG)?

In response to the dramatic decline in England’s biodiversity there are now national targets that aim to significantly improve the condition of natural systems. Other policy ambitions sometimes need to be adapted to contribute to these nature targets. To address the current housing crisis, the UK government has proposed to build 1.5 million new homes by 2029 (The Labour Party, 2024). This housing target sits alongside ambitious targets within the Environment Improvement Plan to halt and reverse declines to nature in England (Defra, 2023). Given that construction is a driver of biodiversity loss, these targets may be in conflict (zu Ermgassen et al., 2022). To reconcile this, developers must apply a measure called Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) (Stuart et al., 2024b).

Brought in via the Environment Act (2021), BNG is a new approach to construction projects (England only). It requires developments to mitigate damage to biodiversity from building and development, and create a measured uplift in biodiversity (DEFRA, 2024). BNG will create a mandatory requirement for nearly all construction projects to measure and improve biodiversity, making it one of the most ambitious ecological compensation policies in the world.

BNG already applies to most building construction projects and will be extended to cover Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs) in May 2026.

The Statutory Biodiversity Metric

For a development to deliver BNG, the Statutory Biodiversity Metric (‘the metric’) (Defra, 2024) is used. The metric is a habitat-based proxy for biodiversity. It is used to measure the biodiversity value before development starts. Post-development, the metric must indicate a 10% improvement in biodiversity value and this improvement must be maintained for at least 30 years. The metric measures biodiversity value by multiplying habitat area by values for habitat distinctiveness and condition, which represent the conservation value and ecological quality of the habitat (Defra, 2024; Duffus et al., 2025a). The metric also assigns higher value to habitats which deliver on the objectives of Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS).

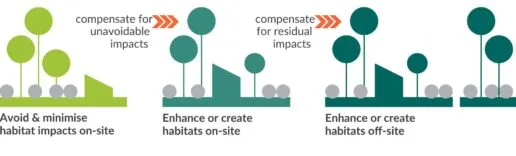

The Biodiversity Gain Hierarchy

Developers must follow the Biodiversity Gain Hierarchy to deliver their BNG commitments.

The hierarchy gives preference to enhancing or creating habitats on-site, i.e. within the development’s footprint, e.g. pond creation or tree planting within a housing estate. When the opportunity for on-site habitats has been exhausted, developers then may turn to delivering BNG off-site. An off-site BNG market now exists with landowners (e.g., farmers) creating biodiversity units to sell by carrying out habitat enhancement and creation on their own land. The off-site BNG market presents a new opportunity for landowners to finance nature recovery activities on their land.

Where developers are unable to deliver BNG on-site or off-site, they can purchase from the government’s statutory credit scheme which pays off their BNG liability. (DEFRA, 2024).

Governance and Compliance

BNG is an offsetting approach, which means that habitats are being destroyed today, while the habitats being created to compensate for the losses may not mature for 5, 10, or even 30 years. The governance of BNG is very important to ensure that those uncertain future gains materialise.

There are key differences in how BNG is governed on-site versus off-site, with differences in transparency and accountability.

Off-site BNG project

Landowners enter a section 106 agreement with a Local Planning Authority (LPA) or a conservation covenant with a responsible body. Agreements secure the gains for at least 30 years. Project details are recorded on a public register alongside any purchases by developers (Defra, 2025a). The combination of the legal instrument and transparency creates a high degree of accountability for off-site BNG projects.

On-site BNG project

Only ‘significant’ on-site gains need to be legally secured for at least 30 years using a section 106 agreement. Significant gains refer to substantial contributions to the total BNG value of a site, e.g. creation of large areas of valuable habitats. All other on-site gains do not need a legal agreement and do not need to be recorded on a public register. This lack of transparency may create a lower degree of accountability for on-site BNG projects.

BNG: The story so far

Within the first 18 months of mandatory BNG, there has been substantial uptake by landowners to deliver off-site BNG projects, with 112 projects registered as of September 2025, promising to deliver over 4,000 hectares of enhanced and created habitat (Defra, 2025a). These projects have the potential to play a role in driving nature recovery in England, contributing to important biodiversity targets. However, research has found that as of June 2025 less than 2% of the land registered as offsets had been sold to development (Duffus et al., 2025b), indicating that demand for off-site units is potentially quite low. Studies from early-adopting BNG councils found that this may be because many developments (particularly larger ones) were able to achieve 10% BNG entirely on-site (zu Ermgassen et al., 2021; Rampling et al., 2023). This is due to the preference for on-site delivery and flexibility in the metric which allows for larger, lower scoring habitats to be traded for smaller, higher scoring habitats. On-site habitats also fall within governance gaps (see above) meaning that gains may not be subject to rigorous compliance monitoring (Chapman et al., 2024).

There has also been a body of research into the ecological outcomes of BNG so far. The habitat-based statutory biodiversity metric has been demonstrated to be an ineffective proxy for wider biodiversity outcomes (Duffus et al., 2025a, 2025c; Hawkins et al., 2022; Marshall et al., 2024). This highlights the need to complement BNG with further species-based monitoring and mitigation. Additionally, there has been a demonstrated skew in the habitats delivered by BNG, with rapidly-maturing, easy to create habitats such as grasslands dominating over more complex, slow maturing habitats including woodlands and wetlands (Duffus et al., 2025b; Miles et al., 2025; Rampling et al., 2023).

Given the prevalence of on-site habitats, BNG is also an important mechanism for delivering greenspace for local communities, although offsetting can be polarising (Apostolopoulou, 2020; Sullivan & Hannis, 2015). Overall, the implementation of BNG increases the acceptability of environmental impacts from developments (Stuart et al., 2024a). However, on a local level, communities’ acceptance of projects is dependent on factors not explicitly incentivised by BNG, such as public access and species richness of habitats (Butler et al., 2025). There can be tensions in delivering offsets which perform well for both nature and people (Mancini et al., 2024), however, it is possible to address these tensions on a project-by-project basis (Atkins et al., 2025).

The future of BNG

Although BNG now applies to most new developments and is expected to come into effect for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs) from May 2026, it remains a dynamic policy. Most recently, Defra ran a consultation on improving the implementation of BNG for minor and medium developments (Defra, 2025b). This consultation included proposals to create blanket exemptions for minor developments and simplifications to the metric for medium developments. These proposals faced criticism for potentially weakening the ecological outcomes of BNG (Leverhulme Centre for Nature Recovery, 2025). BNG also sits alongside proposed planning reform via the Planning and Infrastructure Bill (PIB) which seeks to streamline the mitigation of environmental harms via a Nature Restoration Fund (NRF) (Planning and Infrastructure Bill, 2025). Given the concern about lessening environmental protections from the PIB (Office for Environmental Protection, 2025), BNG remains an important tool for delivering compensation for habitat destruction. Beyond England, BNG is a globally influential policy, with adaptions of the statutory biodiversity metric being created for many countries, including Sweden, Oman, Saudi Arabia, the U.S. and Singapore (Duffus et al., 2025a).

References

- Apostolopoulou, E. (2020) Beyond post-politics: Offsetting, depoliticisation, and contestation in a community struggle against executive housing. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 45, 345–361.

- Atkins, T.B., Duffus, N.E., Butler, A.J., Nicholas, H.C., Ermgassen, S.O.S.E. zu, Addison, P., et al. (2025) A pragmatic framework for local operationalisation of national-level biodiversity impact mitigation commitments.

- Butler, A., Groom, B. & Milner-Gulland, E.J. (2025) Local People’s Preferences for Housing Development-associated Biodiversity Net Gain in England.

- Chapman, K. Tait, M. & Postlethwaite, S. (2024) Lost Nature – housing developers fail to deliver their ecological commitments. Wild Justice.

- Defra. (2023) Environment Improvement Plan 2023. HM Government.

- DEFRA. (2024) Biodiversity net gain. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/biodiversity-net-gain [accessed on 22 February 2024].

- Defra. (2024) Statutory biodiversity metric tools and guides. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/statutory-biodiversity-metric-tools-and-guides [accessed on 12 February 2024].

- Defra. (2025a) Biodiversity Gain Site Register. GOV.UK. https://environment.data.gov.uk/biodiversity-net-gain [accessed on 2025].

- Defra. (2025b) Improving the implementation of Biodiversity Net Gain for minor, medium and brownfield development.

- Duffus, N., Atkins, T., Ermgassen, S. zu, Grenyer, R., Bull, J., Castell, D., et al. (2025a) Data from: A globally influential area-condition metric is a poor proxy for invertebrate biodiversity.

- Duffus, N.E., Ermgassen, S.O.S.E. zu, Grenyer, R. & Lewis, O.T. (2025b) Early outcomes of England’s new biodiversity offset market.

- Duffus, N.E., Lewis, O.T., Grenyer, R., Comont, R.F., Goddard, D., Goulson, D., et al. (2025c) Leveraging Biodiversity Net Gain to address invertebrate declines in England. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 18, 485–493.

- Ermgassen, S.O.S.E. zu, Drewniok, M.P., Bull, J.W., Corlet Walker, C.M., Mancini, M., Ryan-Collins, J., et al. (2022) A home for all within planetary boundaries: Pathways for meeting England’s housing needs without transgressing national climate and biodiversity goals. Ecological Economics, 201, 107562.

- Ermgassen, S.O.S.E. zu, Marsh, S., Ryland, K., Church, E., Marsh, R. & Bull, J.W. (2021) Exploring the ecological outcomes of mandatory biodiversity net gain using evidence from early‐adopter jurisdictions in England. Conservation Letters, 14.

- Hawkins, I., Ermgassen, S.O.S.E. zu, Grub, H., Treweek & Milner-Gulland, E.J. (2022) No Consistent Relationship Found Between Biodiversity Metric Habitat Scores and the Presence of Species of Conservation Priority. Inpractice, 16–20.

- Leverhulme Centre for Nature Recovery. (2025) Defra consultation on improving the implementation of Biodiversity Net Gain for minor, medium and brownfield development: comments from the Leverhulme Centre for Nature Recovery.

- Mancini, M.C., Collins, R.M., Addicott, E.T., Balmford, B.J., Binner, A., Bull, J.W., et al. (2024) Biodiversity offsets perform poorly for both people and nature, but better approaches are available. One Earth, 7, 2165–2174.

- Marshall, C.A.M., Wade, K., Kendall, I.S., Porcher, H., Poffley, J., Bladon, A.J., et al. (2024) England’s statutory biodiversity metric enhances plant, but not bird nor butterfly, biodiversity. Journal of Applied Ecology, n/a.

- Miles, N., Duffus, N.E., Bull, J.W. & Ermgassen, S.O.S.E. zu. (2025) An influential biodiversity market may not direct investment towards habitats of national importance.

- Office for Environmental Protection. (2025) OEP gives advice to Government on the Planning and Infrastructure Bill | Office for Environmental Protection. https://www.theoep.org.uk/report/oep-gives-advice-government-planning-and-infrastructure-bill [accessed on 2025].

- Planning and Infrastructure Bill. (2025).

- Rampling, E.E., Ermgassen, S.O.S.E. zu, Hawkins, I. & Bull, J.W. (2023) Achieving biodiversity net gain by addressing governance gaps underpinning ecological compensation policies. Conservation Biology, n/a.

- Stuart, A., Bond, A. & Franco, A. (2024a) Public Opinions of a Net Outcome Policy: The Case of Biodiversity Net Gain in England.

- Stuart, A., Bond, A., Franco, A., Gerrard, C., Baker, J., Kate, K. ten, et al. (2024b) How England got to Mandatory Biodiversity Net Gain: A Timeline.

- Sullivan, S. & Hannis, M. (2015) Nets and frames, losses and gains: Value struggles in engagements with biodiversity offsetting policy in England. Ecosystem Services, 15, 162–173.

- The Labour Party. (2024) Kickstart economic growth. The Labour Party. https://labour.org.uk/change/kickstart-economic-growth/ [accessed on 2024].