The Rights of Nature (RoN) movement has implications that stretch beyond ecology and culture. By recognising ecosystems as rights-holders, we open the door to new models of economics, new financial tools and new forms of governance that prioritise regeneration over extraction. If current models are driving climate breakdown and biodiversity loss, then redesigning economics, finance and governance to serve life is not radical – it is necessary.

RoN for a doughnut-shaped economy

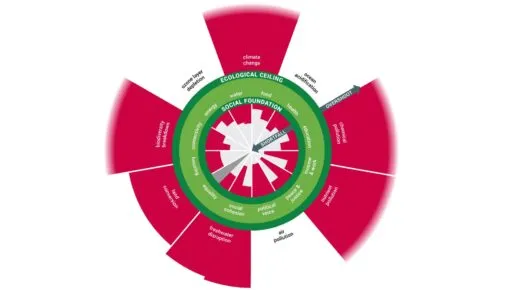

One influential framework that aligns closely with the RoN movement is economist Kate Raworth’s concept of Doughnut Economics. The model (see Figure below) envisions a “safe and just space” for humanity, represented as the area between two concentric rings. The inner ring, representing a social foundation, defines the minimum conditions for human wellbeing. Falling below this threshold means people are deprived of essential needs. The outer ring represents the ecological ceiling, which marks the limits of planetary boundaries, and overshooting this ceiling undermines ecological stability. The safe space between these two boundaries is where both people and planet can thrive.

Protecting the rights of nature supports this model because when ecosystems have rights to exist and thrive, they are safeguarded from destructive exploitation, which keeps us inside the ecological ceiling. At the same time, many RoN initiatives restore Indigenous-led governance, promoting equity and resilience, helping us avoid the social “hole” of the Doughnut. In other words, recognising nature’s rights can push us closer to prosperity that is both fair and sustainable.

Moving beyond GDP

The cultural shift inspired by the movement also forces us to confront deeper questions: should endless GDP growth remain the central goal of development, even when it so often conflicts with ecological limits? As Kate Raworth argues in Doughnut Economics, we should redefine the economic goal as “human prosperity in a flourishing web of life” – and recognising nature’s rights is certainly a step towards that aim. It asks us to measure success differently: not just in dollars and growth rates, but in ecosystem health, resilience, and long-term functioning.

Rethinking the human portrait

The cultural shift inspired by the RoN movement can prompt a redefinition of how economics portrays people. Traditional economic models often reduce humans to agents of unlimited desire: as mere consumers. As economist Robert Frank observed, “our beliefs about human nature help shape human nature itself.” By narrowing our identity, these models have fuelled a culture of extraction and overconsumption.

The RoN movement challenges that story. By restoring our connection to nature, it can help us reimagine humans not just as consumers but as participants in a web of life, motivated by care, reciprocity, and stewardship. That shift in self-image could ripple through how we design policies, economies, and even our everyday choices.

Finance in service of life

Surprisingly, the movement is also beginning to influence finance. A remarkable example is the Moananui Sanctuary Trust in the Pacific. Guided by principles like tauhi fonua (caring for land and ocean) and a deep sense of interconnectedness, the Trust seeks to confer legal personhood on whales. This comes as a way of expressing the kinship between makapuna (grandchildren, which are the stewards of the ocean), the whales and the Moananui (big ocean).

To achieve this and broader goals, including investment into Indigenous-led sanctuary management through ocean habitat restoration, the Trust set up the Pacific Whale Fund and the Moananui Living Oceans Vehicle to deliver it. The comprehensive framework Moananui Blueprint: Ocean Finance for a Resilient Pacific outlines innovative tools -whale insurance, blue bonds, nature credits- aimed at raising €100 million for marine restoration.

Here, the RoN movement directly inspires financial systems designed to regenerate ecosystems, not exploit them. It shows how local philosophies, when scaled and supported, can spark systemic global changes.

Scaling up: beyond Indigenous contexts

Many RoN initiatives grow out of Indigenous advocacy. That raises a practical question: how can the movement scale in places where traditional lifeways have been displaced?

One answer lies in the cultural shift RoN promotes. Ideas spread as a result of network effects, seeding inspiration even in regions where Indigenous governance has been eroded. In the UK, for example, a popular nature author, Robert Macfarlane, is leading the movement, backed by his most recent book: Is a River Alive?. Furthermore, scientists are experimenting with new ways to make nature’s voice more apparent. For example, new web apps allow users to ‘talk‘ to trees: sensors embedded in bark detect chemical signals that are translated by artificial intelligence into outputs readable for humans. These “conversations” with trees may sound futuristic, but they how technology can help us reconnect with the living world, recognise its aliveness, and, by extension, its rights.

Intelligence beyond humans

Skeptics of the movement argue that legal rights should be reserved to humans given our unique intelligence and ability of complex language. However, when we deepen our understanding of the living world, the abundance of non-human intelligence becomes clear.

The More-Than-Human Life (MOTH) Programme at NYU and Project CETI (Cetacean Translation Initiative) are using artificial intelligence and bioacoustics to uncover the complexities of non-human communication, such as evidence of a sperm whale phonetic alphabet. When combined with Indigenous wisdom, such breakthroughs strengthen the case for expanding global legal recognition to non-human life.

To conclude, recognising the rights of nature is not only a legal or cultural innovation, but also a powerful catalyst for reshaping economies and finance to serve life rather than deplete it. By embracing this shift, we open the possibility of building economies that regenerate ecosystems, honour Indigenous wisdom, and secure prosperity within planetary boundaries.

Suggested reading: